- Health and hygiene, schools and other non-household settings

- Nutrition and WASH (including stunted growth)

- Advocacy and events on WASH & Nutrition

- Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

17.2k views

Re: Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

Dear all,

There is overwhelming evidence that the prevalence of malnutrition among children up to age 5 has not declined over the past decade. This is also borne out by the Rapid Survey of Children (RSOC) in 2013-14 by the Ministry of Women and Child Development. If anything, the RSOC detected higher rates of underweight and stunted children than the National Family Health Surveys (32% stunted in RSOC against 23.3% in NFHS 4 and 22.5% in NFHS 5).

Government figures show that even now, about a third of total 1.36 million anganwadi centres have neither toilets nor drinking water facilities, according to a Parliamentary panel report tabled in March 2018. Nearly 25 per cent of the centres don’t have drinking water facilities and 36 per cent don’t have toilets.

The lowest percentage lacking drinking water is in Manipur where only 21 per cent AWCs have drinking water facilities followed by Arunachal Pradesh (28.51 per cent), Uttarakhand (29.04 per cent), Karnataka (38.76 per cent), Telangana (40.21 per cent), Jammu and Kashmir (48.18 per cent) and Maharashtra (53.47 per cent) as per the report. In Telanagana only 21.30 per cent AWCs have toilets, followed by Manipur (27.05 per cent), Jharkhand (38.74 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (43.93 per cent), Jammu and Kashmir cent), Jharkhand (38.74 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (43.93 per cent), Jammu and Kashmir (44.11 per cent), Assam (47.51 per cent), Arunachal Pradesh (48.73 per cent) and Odisha (52.64 per cent).

90 per cent migrant children do not have access to ICDS and Anganwadi services (Status of 90 per cent migrant children do not have access to ICDS and Anganwadi services.

There are many points of convergence already laid out in the policies that govern the nutrition, anganwadi and WASH programmes. But clearly their implementation in the field is below par. Perhaps one reason is that a third of anganwadis are in rented buildings and the government is reluctant to invest in building infrastructure in these buildings.

There would be other reasons for these gaps. and it would be great if you could provide state-specific insights.

Regards,

Nitya

There is overwhelming evidence that the prevalence of malnutrition among children up to age 5 has not declined over the past decade. This is also borne out by the Rapid Survey of Children (RSOC) in 2013-14 by the Ministry of Women and Child Development. If anything, the RSOC detected higher rates of underweight and stunted children than the National Family Health Surveys (32% stunted in RSOC against 23.3% in NFHS 4 and 22.5% in NFHS 5).

Government figures show that even now, about a third of total 1.36 million anganwadi centres have neither toilets nor drinking water facilities, according to a Parliamentary panel report tabled in March 2018. Nearly 25 per cent of the centres don’t have drinking water facilities and 36 per cent don’t have toilets.

The lowest percentage lacking drinking water is in Manipur where only 21 per cent AWCs have drinking water facilities followed by Arunachal Pradesh (28.51 per cent), Uttarakhand (29.04 per cent), Karnataka (38.76 per cent), Telangana (40.21 per cent), Jammu and Kashmir (48.18 per cent) and Maharashtra (53.47 per cent) as per the report. In Telanagana only 21.30 per cent AWCs have toilets, followed by Manipur (27.05 per cent), Jharkhand (38.74 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (43.93 per cent), Jammu and Kashmir cent), Jharkhand (38.74 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (43.93 per cent), Jammu and Kashmir (44.11 per cent), Assam (47.51 per cent), Arunachal Pradesh (48.73 per cent) and Odisha (52.64 per cent).

90 per cent migrant children do not have access to ICDS and Anganwadi services (Status of 90 per cent migrant children do not have access to ICDS and Anganwadi services.

There are many points of convergence already laid out in the policies that govern the nutrition, anganwadi and WASH programmes. But clearly their implementation in the field is below par. Perhaps one reason is that a third of anganwadis are in rented buildings and the government is reluctant to invest in building infrastructure in these buildings.

There would be other reasons for these gaps. and it would be great if you could provide state-specific insights.

Regards,

Nitya

Please Log in to join the conversation.

You need to login to reply- sunetralala

-

Less

Less- Posts: 17

- Karma: 1

- Likes received: 6

Re: Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

Dear all

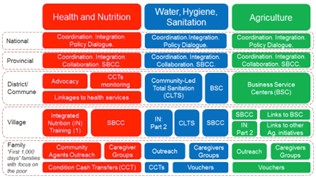

I serve as the WASH Sector Leader with SNV in Nepal. Previously, I served as the WASH Sector Leader in Cambodia where I managed the WASH component of a project called NOURISH (June 2014 – June 2020) that assisted the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) in reducing stunting by focusing on key determinants of chronic malnutrition. NOURISH took a multi-sectorial approach integrating health/nutrition, WASH and agriculture. NOURISH aimed to improve market functioning, so that WASH and agriculture products and services were available for a variety of consumer needs and preferences and accessible and affordable to significantly more customers in the project-supported geographical areas.

The Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey in 2014 showed that one out of three (32%) children under the age of five were stunted. The prevalence of stunting was 10% higher among children born to mothers from the lowest wealth quintile (42%) (CDHS, 2014). The RGC made a commitment to address the nutrition and stunting challenge, and reverse its effects by focusing on the most vulnerable and poor food-insecure households.

NOURISH used four strategies:

NOURISH developed a social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) campaign called ‘Grow Together’, based on a formative research, that united WASH and nutrition behaviours under a single brand. The campaign connected rural families, health workers, community WASH and health volunteers, leaders, and local businesses together for child growth with tailored messages for them,

across WASH and health/nutrition.

It brought out 13 behaviours covering WASH, nutrition and health with “first 1,000 days” families at its core. Grow Together aimed to improve nutrition during pregnancy through improved diet and antenatal care. For children, the campaign promoted attendance at monthly nutrition services, exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months continuing for up to 2 years, along with optimal feeding from 6-23 months.

To boost food and nutrition security, the campaign encouraged methods to increase access to nutritious foods year-round by setting up micro-gardens, collecting nutritious food around the home, and preserving and storing fish for children and pregnant women. With WASH, the campaign promoted drinking clean water (using water filters), construction of improved latrines (through CLTS campaigns and supply chain support), washing hands with soap at critical times, as well as separating animals from small children and properly disposing of infant faeces.

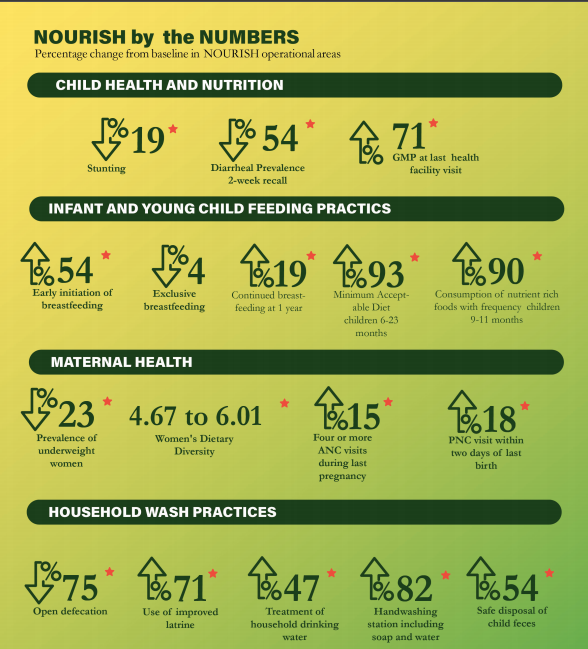

To assess its overall impact, NOURISH implemented a baseline survey (November 2015) and an endline survey (November 2018). The results are in Figure 2 (attached). The assessment showed many positive results across key health, nutrition, WASH, and agriculture indicators as enumerated in the figure.

Regards

Sunetra Lala

WASH Sector Leader

SNV Nepal

I serve as the WASH Sector Leader with SNV in Nepal. Previously, I served as the WASH Sector Leader in Cambodia where I managed the WASH component of a project called NOURISH (June 2014 – June 2020) that assisted the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) in reducing stunting by focusing on key determinants of chronic malnutrition. NOURISH took a multi-sectorial approach integrating health/nutrition, WASH and agriculture. NOURISH aimed to improve market functioning, so that WASH and agriculture products and services were available for a variety of consumer needs and preferences and accessible and affordable to significantly more customers in the project-supported geographical areas.

The Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey in 2014 showed that one out of three (32%) children under the age of five were stunted. The prevalence of stunting was 10% higher among children born to mothers from the lowest wealth quintile (42%) (CDHS, 2014). The RGC made a commitment to address the nutrition and stunting challenge, and reverse its effects by focusing on the most vulnerable and poor food-insecure households.

NOURISH used four strategies:

- strengthen community delivery platforms to support integrated nutrition;

- create demand for health, WASH, and agriculture practices, services, and products;

- expand supply of health, WASH and agriculture products using the private sector, and;

- enhance government and civil society capacity in integrated nutrition (see Figure 1).

NOURISH developed a social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) campaign called ‘Grow Together’, based on a formative research, that united WASH and nutrition behaviours under a single brand. The campaign connected rural families, health workers, community WASH and health volunteers, leaders, and local businesses together for child growth with tailored messages for them,

across WASH and health/nutrition.

It brought out 13 behaviours covering WASH, nutrition and health with “first 1,000 days” families at its core. Grow Together aimed to improve nutrition during pregnancy through improved diet and antenatal care. For children, the campaign promoted attendance at monthly nutrition services, exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months continuing for up to 2 years, along with optimal feeding from 6-23 months.

To boost food and nutrition security, the campaign encouraged methods to increase access to nutritious foods year-round by setting up micro-gardens, collecting nutritious food around the home, and preserving and storing fish for children and pregnant women. With WASH, the campaign promoted drinking clean water (using water filters), construction of improved latrines (through CLTS campaigns and supply chain support), washing hands with soap at critical times, as well as separating animals from small children and properly disposing of infant faeces.

To assess its overall impact, NOURISH implemented a baseline survey (November 2015) and an endline survey (November 2018). The results are in Figure 2 (attached). The assessment showed many positive results across key health, nutrition, WASH, and agriculture indicators as enumerated in the figure.

Regards

Sunetra Lala

WASH Sector Leader

SNV Nepal

Attachments:

Please Log in to join the conversation.

You need to login to reply- AjitSeshadri

-

- Marine Chief Engineer by profession (1971- present) and at present Faculty in Marine Engg. Deptt. Vels University, Chennai, India. Also proficient in giving Environmental solutions , Designation- Prof. Ajit Seshadri, Head- Environment, The Vigyan Vijay Foundation, NGO, New Delhi, INDIA , Consultant located at present at Chennai, India

Re: Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

Dear SuSanA Members:

2nd Question or issue on curative / remedial methods.

Hand wash and personal hygiene is to be ensured..

Towards this apt IEC / IPC effective sessions are needed in communities, commencing best from School level.

Children going to school, need to be made aware of good practices on personal hygiene and upkeep of infra facilities.

We do note, that there are many PHCs and others, without water supply, electric power and privacy Etc.

The Teachers, others need to educate them.

With well wishes.

Prof Ajit Seshadri

Vigyan Vijay Foundation Ngo

2nd Question or issue on curative / remedial methods.

Hand wash and personal hygiene is to be ensured..

Towards this apt IEC / IPC effective sessions are needed in communities, commencing best from School level.

Children going to school, need to be made aware of good practices on personal hygiene and upkeep of infra facilities.

We do note, that there are many PHCs and others, without water supply, electric power and privacy Etc.

The Teachers, others need to educate them.

With well wishes.

Prof Ajit Seshadri

Vigyan Vijay Foundation Ngo

Prof. Ajit Seshadri, Faculty in Marine Engg. Deptt. Vels University, and

Head-Environment , VigyanVijay Foundation, Consultant (Water shed Mngmnt, WWT, WASH, others)Located at present at Chennai, India

Head-Environment , VigyanVijay Foundation, Consultant (Water shed Mngmnt, WWT, WASH, others)Located at present at Chennai, India

Please Log in to join the conversation.

You need to login to reply- AjitSeshadri

-

- Marine Chief Engineer by profession (1971- present) and at present Faculty in Marine Engg. Deptt. Vels University, Chennai, India. Also proficient in giving Environmental solutions , Designation- Prof. Ajit Seshadri, Head- Environment, The Vigyan Vijay Foundation, NGO, New Delhi, INDIA , Consultant located at present at Chennai, India

Re: Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

Dear SuSanA Members:

Subject: Responses on the 2 aspects :

1st one being preventive type, when communities were doing ODF, SBM managed to make toilets for needy.

At a few sites, due infra problems were not able to make CTCs and at some spaces, they were made, and were not used for Toilet and sanitation purposes.

Hence the ODF condition were not fully complied with , and OD persisted in some spaces.

It is at these spaces, a via media approach is planned, ie C O D : Meaning Controlled open defecation practices, ie OD practice is carried out by communities in one site, and an another space rightly sized L by W , is allocated near the earlier one.

These 2 spaces are duly marked for" men only..Etc" and are used alternately..

One space used for 3 to 4 weeks and the other used for cleaning, upkeep and maintenance.

It is at these spaces, human sludges are manually cleaned and Co composted in the same site for a month say..

Twin spaces identical in size are allocated for 1. Men only, 2. Women only 3. Others ie children accompanied by mothers and special needs persons Etc.

These practices have been earlier in service, during flood- relief at Kerala State, Maha kumbh time at Prayag as reported by CEPT, Bulletin .

Result of these practices would be precisely for :

Faecal matter and its effects, leading to oral transmission at OD regions will be greatly reduced..

Well wishes to communities.

Prof Ajit Seshadri,

Vigyan Vijay Foundation Ngo

Subject: Responses on the 2 aspects :

1st one being preventive type, when communities were doing ODF, SBM managed to make toilets for needy.

At a few sites, due infra problems were not able to make CTCs and at some spaces, they were made, and were not used for Toilet and sanitation purposes.

Hence the ODF condition were not fully complied with , and OD persisted in some spaces.

It is at these spaces, a via media approach is planned, ie C O D : Meaning Controlled open defecation practices, ie OD practice is carried out by communities in one site, and an another space rightly sized L by W , is allocated near the earlier one.

These 2 spaces are duly marked for" men only..Etc" and are used alternately..

One space used for 3 to 4 weeks and the other used for cleaning, upkeep and maintenance.

It is at these spaces, human sludges are manually cleaned and Co composted in the same site for a month say..

Twin spaces identical in size are allocated for 1. Men only, 2. Women only 3. Others ie children accompanied by mothers and special needs persons Etc.

These practices have been earlier in service, during flood- relief at Kerala State, Maha kumbh time at Prayag as reported by CEPT, Bulletin .

Result of these practices would be precisely for :

Faecal matter and its effects, leading to oral transmission at OD regions will be greatly reduced..

Well wishes to communities.

Prof Ajit Seshadri,

Vigyan Vijay Foundation Ngo

Prof. Ajit Seshadri, Faculty in Marine Engg. Deptt. Vels University, and

Head-Environment , VigyanVijay Foundation, Consultant (Water shed Mngmnt, WWT, WASH, others)Located at present at Chennai, India

Head-Environment , VigyanVijay Foundation, Consultant (Water shed Mngmnt, WWT, WASH, others)Located at present at Chennai, India

Please Log in to join the conversation.

You need to login to reply- arundatimd

-

Less

- Posts: 4

- Likes received: 1

Re: Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

The National Family Health Survey (NHFS) – 5 (2019-2020) starkly underscored that despite efforts on multiple fronts, there has been limited improvements in child malnutrition in several States. This comes at the heals of significant investments in two country wide initiatives. The POSHAN Abhiyan, the Government of India’s flagship initiative, aimed to improve health and nutrition status among children, adolescent girls and women. The Swachh Bharat Mission catalysed action on safe sanitation in the country and resulted in India being declared open defecation free in October 2019, with critical implications for public health, particularly child health. So why have improvements in undernutrition been limited? One lens to examine this puzzle may be through the lens of convergence. Development programs of the Government and non-Government interventions have stressed convergence to achieve outcomes related to health, nutrition, education, among other issues. Yet, operationalization and financing of convergence has been weak. Perhaps one reason for the lack of operational convergence is the need for more guidance on how convergence can be brought about, with a focus on different levels or intensities of convergence.

A useful framework to interpret and actualize convergence is in terms of integration. Integration can occur along a continuum. Below, I outline three possible phases:

1) The most basic level of integration is Co- locating or co-targeting – overlapping delivery of WASH and nutrition activities in the same geographical area and with the same populations, towards a common objective, but with separate implementation. This involves sharing information across programmes and ministries, which require some coordination and sharing of information or data to inform planning and targeting of services. In terms of who to reach or target, groups who have poor nutritional status, including pregnant women, mothers, adolescents and children under five (especially the 1,000-day window from conception to age two years), but ensuring an approach to reach universal access. For WASH, ensuring universal WASH in a community will be critical for widespread and sustained benefits.

2) At a second, deeper level, integration involves enhancing the sensitivity of programs to the links between WASH and nutrition. This can be done by incorporating elements of nutrition into WASH programs (e.g., hygiene promotion in schools WASH interventions to emphasize hygiene behaviors related to health and nutrition such as handwashing, safe disposal of child faeces, safe drinking water), and/or by incorporating elements of WASH into nutrition programs (e.g., nutrition interventions like mid-day meal, or de-worming to promote toilet use, safe management of child faeces, and handwashing with soap with relevant target groups).

3) At the deepest level is integrated or joint programming, where by hygiene promotion (handwashing, food hygiene, safe disposal of child faeces, environmental hygiene) is embedded in the delivery of nutrition programs at various levels (individual, household, community, institutions). Nutrition programs must ensure access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene services to target populations through close collaboration with relevant departments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has deeply affected populations, particularly those who have pre-existing socio-economic vulnerabilities. The time for integrated service delivery for health, nutrition and WASH is now to combat the adverse impacts of the pandemic, and to promote and safeguard the health of millions of young children, girls and women.

In this discussion, we invite you to share:

1) How you or your organization have fostered convergence or integration, emphasizing the programmatic approaches, budgetary allocations, institutional mechanisms deployed.

2) How have you informed policy at the state or national level towards integration?

3) How have your assessed/evaluated integrated programs on nutrition and WASH? Any specific indicators and tools used?

A useful framework to interpret and actualize convergence is in terms of integration. Integration can occur along a continuum. Below, I outline three possible phases:

1) The most basic level of integration is Co- locating or co-targeting – overlapping delivery of WASH and nutrition activities in the same geographical area and with the same populations, towards a common objective, but with separate implementation. This involves sharing information across programmes and ministries, which require some coordination and sharing of information or data to inform planning and targeting of services. In terms of who to reach or target, groups who have poor nutritional status, including pregnant women, mothers, adolescents and children under five (especially the 1,000-day window from conception to age two years), but ensuring an approach to reach universal access. For WASH, ensuring universal WASH in a community will be critical for widespread and sustained benefits.

2) At a second, deeper level, integration involves enhancing the sensitivity of programs to the links between WASH and nutrition. This can be done by incorporating elements of nutrition into WASH programs (e.g., hygiene promotion in schools WASH interventions to emphasize hygiene behaviors related to health and nutrition such as handwashing, safe disposal of child faeces, safe drinking water), and/or by incorporating elements of WASH into nutrition programs (e.g., nutrition interventions like mid-day meal, or de-worming to promote toilet use, safe management of child faeces, and handwashing with soap with relevant target groups).

3) At the deepest level is integrated or joint programming, where by hygiene promotion (handwashing, food hygiene, safe disposal of child faeces, environmental hygiene) is embedded in the delivery of nutrition programs at various levels (individual, household, community, institutions). Nutrition programs must ensure access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene services to target populations through close collaboration with relevant departments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has deeply affected populations, particularly those who have pre-existing socio-economic vulnerabilities. The time for integrated service delivery for health, nutrition and WASH is now to combat the adverse impacts of the pandemic, and to promote and safeguard the health of millions of young children, girls and women.

In this discussion, we invite you to share:

1) How you or your organization have fostered convergence or integration, emphasizing the programmatic approaches, budgetary allocations, institutional mechanisms deployed.

2) How have you informed policy at the state or national level towards integration?

3) How have your assessed/evaluated integrated programs on nutrition and WASH? Any specific indicators and tools used?

Please Log in to join the conversation.

You need to login to replyThematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

Dear all,

We are starting a thematic discussion on the need for convergence between WASH and Nutrition programmes on the SuSanA India Chapter. Arundati Muralidharan, policy manager at WaterAid India, will be anchor the discussion.

Background

The role of water, sanitation,and hygiene in preventing disease is clearly not new, yet the attention this critical determinant of health has received from the health sector is underwhelming. Almost 170 years ago, Ignaz Semmelweis (the “Saviour of mothers”) found that high rates of infection and consequent deaths among new mothers in a Vienna hospital could be significantly reduced if health care providers washed their hands with chlorinated lime solution. Louis Pasteur postulated we drink 90 per cent of our diseases. In London (1848) John Snow drew attention to the role of contaminated water and poor waste management systems in fueling a deadly cholera outbreak.

India continues to face pressing health issues. High rates of maternal mortality, as well as diarrheal diseases, pneumonia, and undernutrition among children makes India one of the global leaders in maternal and child morbidity and mortality. The common risk factors across these conditions are unsafe WASH practices. Handwashing, the basic hygiene practice, is only practiced by 60 per cent of Indians, a figure that has remained unchanged since 2015 while 66 per cent have access to an improved water source and 46 per cent to safely managed sanitation[1].

The Question

So how does WASH effect such a diverse range of health conditions? Economist Dean Spears articulates a strong connection between open defecation and stunting among Indian children - faecal pathogens ingested by children (through any of the pathways) cause diarrhoea and environmental enteropathy, which inhibits the intestines from absorbing essential nutrients. As a result, children fail to grow and thrive (Spears et al). Equally important is the presence, quality and use of WASH in health care facilities. Hygiene practices, especially handwashing by health care providers and physical cleanliness of patient care and clinical areas, is connected with hospital acquired infections (Alegrazi et al). The WHO and UNICEF 2015 report on the status of WASH in health care facilities in low- and middle-income countries highlights that only 72 per cent of health facilities in India have water and 59 per cent have sanitation facilities (WHO and UNICEF). But these figures refer only to the presence of facilities not to their quality and use.

Health facility assessments by WaterAid in four states (2014-2015) highlight that while WASH infrastructure may exist in health facilities, the quantity and quality of water is grossly deficient, toilets are in bad condition and often unusable, and handwashing stations are dysfunctional (e.g., no soap to wash hands, no running water in taps). Particularly alarming are the varied levels of awareness and low levels of practice among health facility staff of hygiene behaviour and infection control and prevention practices.

Women and girls are vulnerable to certain health conditions when they lack access to safe WASH facilities. Research in Odisha found that pregnant women who defecated in the open were at significantly higher risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes and pre-term birth (Padhi et al). Furthermore, girls and women reported feelingfearful and anxious that they might experience sexual harassment or violence when they defecate in the open, have to walk a distance to access a toilet, or when available toilets are unsafe (Kulkarni and O’Reilly, Lennon). There are two aspects to the issue.

Two Aspects

The first, preventive aspect, deals with good WASH practices by the public to prevent faecal-oral transmission, whereby germs (from open defecation and poor hygiene) are transmitted through five pathways. Incidentally, transmission via fingers is a high-risk factor for COVID-19 as well.

The latest National Family Health Survey(Fifth Round, 2019-2020) indicates that in 22 states for which data is available, the incidence of diarrhoea in children has increased compared to the last NHFS in 2015-16[2]. This is despite an increase in access to toilets in the country in the same period. With 38.4 per cent of children under the age of five stunted, India has among the highest number of children who are short for their age in the world, a marker for hampered physical and cognitive growth[3].

The second, curative aspect, deals with the WASH infrastructure and behaviour in health centres. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP 2019[4]) indicates WASH services in health care facilities are sub-standard in every region. This is a major contributor to maternal mortality.[5]

Even though WASH and Health are inextricably linked, policies and programmes of the two are usually unconnected. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to bring these two sectors together given the central role of good hygiene practices such as handwashing with soap and WASH in health care facilities in preventing infections. If they converge and reach children, they offer greater efficiencies and impact. The same is true for joint advocacy.

The health sector must take heed of the wide-ranging impacts of WASH on health in terms of promoting good health, preventing disease, curing conditions, and complementing palliative and rehabilitative services. During the Swachh Bharat Mission toilet coverage increased substantially in India. The Swachhata Guidelines for health facilities (also known as Kaya Kalp Guidelines) launched in 2015 were another effort to address WASH in health care facilities, having the potential to fill a critical, though largely ignored, infrastructure gap in the delivery of health services.

Yet this effort must go beyond building or improving WASH infrastructure in health facilities to include concerted action on enhancing hygiene behaviour, especially handwashing by health care providers and caregivers, and maintaining cleanliness in clinical and patient care areas in facilities.

A human-centred approach to understanding reasons for poor hygiene practices and how they can be improved will by of more help than conventional approaches centred on IEC or IPC. This places people at the centre of the problem and works out possible solutions from that perspective, rather than a WASH or health practitioner’s perspective. It also considers the user experience of all concerned – doctors, nurses, attendants, patients and their relatives – to help design an intervention method.

During the COVID-19 pandemic key hygiene practices that are an integral part of WASH has been promoted as the first line of defence against infection. Handwashing is the most important of such practices followed by disinfection of surfaces, safe storage of water and the usage of toilets. These reduce the chances of picking up the infection by cutting the transmission pathways from the host is much the same way as shown in Figure 1. Earlier this month, SuSanA conducted a thematic discussion and webinar on promoting COVID appropriate behaviour.

The Discussion

These practices acquire more significance in health centres that see a high footfall of people with COVID-19 infections. Not only are they critical to reduce HAIs, they prevent transmission to health staff. It is critical for health staff and administrators to ensure these behaviours become ‘sticky’.

Accordingly, this discussion will attempt to understand linkages between the preventive and curative aspects of health and WASH, and tease out what prevents them from working together. Finally, it will explore ways to converge programmes in these two areas.

Its objectives are

We had conducted a webinar on 6 August on the topic. Its summary is available here - forum.susana.org/285-advocacy/24959-summ...d-wash-and-nutrition.

[1]Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: Five years into the SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

[2]International Institute for Population Studies, 2020. National Family Health Survey Round 5, Key Indicators from 22 states, rchiips.org/NFHS/NFHS-5_FCTS/NFHS-5%20St...mpendium_Phase-I.pdf

[3]Arundati Muralidharan, 2019. The interlinkages between water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and nutrition, WaterAid India, New Delhi.

[4] World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund, WASH in healthcare facilities: Global Baseline Report 2019, WHO and UNICEF, Geneva,2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

[5]Benova et all (2014) Systematic review and meta-analysis”: association between water and sanitation environment and maternal mortality. Trop Med and Intl Health. 19: 368 - 38

We are starting a thematic discussion on the need for convergence between WASH and Nutrition programmes on the SuSanA India Chapter. Arundati Muralidharan, policy manager at WaterAid India, will be anchor the discussion.

Background

The role of water, sanitation,and hygiene in preventing disease is clearly not new, yet the attention this critical determinant of health has received from the health sector is underwhelming. Almost 170 years ago, Ignaz Semmelweis (the “Saviour of mothers”) found that high rates of infection and consequent deaths among new mothers in a Vienna hospital could be significantly reduced if health care providers washed their hands with chlorinated lime solution. Louis Pasteur postulated we drink 90 per cent of our diseases. In London (1848) John Snow drew attention to the role of contaminated water and poor waste management systems in fueling a deadly cholera outbreak.

India continues to face pressing health issues. High rates of maternal mortality, as well as diarrheal diseases, pneumonia, and undernutrition among children makes India one of the global leaders in maternal and child morbidity and mortality. The common risk factors across these conditions are unsafe WASH practices. Handwashing, the basic hygiene practice, is only practiced by 60 per cent of Indians, a figure that has remained unchanged since 2015 while 66 per cent have access to an improved water source and 46 per cent to safely managed sanitation[1].

So how does WASH effect such a diverse range of health conditions? Economist Dean Spears articulates a strong connection between open defecation and stunting among Indian children - faecal pathogens ingested by children (through any of the pathways) cause diarrhoea and environmental enteropathy, which inhibits the intestines from absorbing essential nutrients. As a result, children fail to grow and thrive (Spears et al). Equally important is the presence, quality and use of WASH in health care facilities. Hygiene practices, especially handwashing by health care providers and physical cleanliness of patient care and clinical areas, is connected with hospital acquired infections (Alegrazi et al). The WHO and UNICEF 2015 report on the status of WASH in health care facilities in low- and middle-income countries highlights that only 72 per cent of health facilities in India have water and 59 per cent have sanitation facilities (WHO and UNICEF). But these figures refer only to the presence of facilities not to their quality and use.

Health facility assessments by WaterAid in four states (2014-2015) highlight that while WASH infrastructure may exist in health facilities, the quantity and quality of water is grossly deficient, toilets are in bad condition and often unusable, and handwashing stations are dysfunctional (e.g., no soap to wash hands, no running water in taps). Particularly alarming are the varied levels of awareness and low levels of practice among health facility staff of hygiene behaviour and infection control and prevention practices.

Women and girls are vulnerable to certain health conditions when they lack access to safe WASH facilities. Research in Odisha found that pregnant women who defecated in the open were at significantly higher risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes and pre-term birth (Padhi et al). Furthermore, girls and women reported feelingfearful and anxious that they might experience sexual harassment or violence when they defecate in the open, have to walk a distance to access a toilet, or when available toilets are unsafe (Kulkarni and O’Reilly, Lennon). There are two aspects to the issue.

Two Aspects

The first, preventive aspect, deals with good WASH practices by the public to prevent faecal-oral transmission, whereby germs (from open defecation and poor hygiene) are transmitted through five pathways. Incidentally, transmission via fingers is a high-risk factor for COVID-19 as well.

The latest National Family Health Survey(Fifth Round, 2019-2020) indicates that in 22 states for which data is available, the incidence of diarrhoea in children has increased compared to the last NHFS in 2015-16[2]. This is despite an increase in access to toilets in the country in the same period. With 38.4 per cent of children under the age of five stunted, India has among the highest number of children who are short for their age in the world, a marker for hampered physical and cognitive growth[3].

The second, curative aspect, deals with the WASH infrastructure and behaviour in health centres. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP 2019[4]) indicates WASH services in health care facilities are sub-standard in every region. This is a major contributor to maternal mortality.[5]

Even though WASH and Health are inextricably linked, policies and programmes of the two are usually unconnected. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to bring these two sectors together given the central role of good hygiene practices such as handwashing with soap and WASH in health care facilities in preventing infections. If they converge and reach children, they offer greater efficiencies and impact. The same is true for joint advocacy.

The health sector must take heed of the wide-ranging impacts of WASH on health in terms of promoting good health, preventing disease, curing conditions, and complementing palliative and rehabilitative services. During the Swachh Bharat Mission toilet coverage increased substantially in India. The Swachhata Guidelines for health facilities (also known as Kaya Kalp Guidelines) launched in 2015 were another effort to address WASH in health care facilities, having the potential to fill a critical, though largely ignored, infrastructure gap in the delivery of health services.

Yet this effort must go beyond building or improving WASH infrastructure in health facilities to include concerted action on enhancing hygiene behaviour, especially handwashing by health care providers and caregivers, and maintaining cleanliness in clinical and patient care areas in facilities.

A human-centred approach to understanding reasons for poor hygiene practices and how they can be improved will by of more help than conventional approaches centred on IEC or IPC. This places people at the centre of the problem and works out possible solutions from that perspective, rather than a WASH or health practitioner’s perspective. It also considers the user experience of all concerned – doctors, nurses, attendants, patients and their relatives – to help design an intervention method.

During the COVID-19 pandemic key hygiene practices that are an integral part of WASH has been promoted as the first line of defence against infection. Handwashing is the most important of such practices followed by disinfection of surfaces, safe storage of water and the usage of toilets. These reduce the chances of picking up the infection by cutting the transmission pathways from the host is much the same way as shown in Figure 1. Earlier this month, SuSanA conducted a thematic discussion and webinar on promoting COVID appropriate behaviour.

The Discussion

These practices acquire more significance in health centres that see a high footfall of people with COVID-19 infections. Not only are they critical to reduce HAIs, they prevent transmission to health staff. It is critical for health staff and administrators to ensure these behaviours become ‘sticky’.

Accordingly, this discussion will attempt to understand linkages between the preventive and curative aspects of health and WASH, and tease out what prevents them from working together. Finally, it will explore ways to converge programmes in these two areas.

Its objectives are

- To understand what correlations exist between improved levels of sanitation and hygiene, and health and nutrition. Also, what are the reasons for adoption of good hygiene practices,or the lack thereof, even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- To collate and consolidate evidence for relatedness and interdependence of the vital health and nutritional indicators with those of WASH

We had conducted a webinar on 6 August on the topic. Its summary is available here - forum.susana.org/285-advocacy/24959-summ...d-wash-and-nutrition.

[1]Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: Five years into the SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

[2]International Institute for Population Studies, 2020. National Family Health Survey Round 5, Key Indicators from 22 states, rchiips.org/NFHS/NFHS-5_FCTS/NFHS-5%20St...mpendium_Phase-I.pdf

[3]Arundati Muralidharan, 2019. The interlinkages between water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and nutrition, WaterAid India, New Delhi.

[4] World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund, WASH in healthcare facilities: Global Baseline Report 2019, WHO and UNICEF, Geneva,2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

[5]Benova et all (2014) Systematic review and meta-analysis”: association between water and sanitation environment and maternal mortality. Trop Med and Intl Health. 19: 368 - 38

The following user(s) like this post: AjitSeshadri, weareraman

Please Log in to join the conversation.

You need to login to reply

Share this thread:

- Health and hygiene, schools and other non-household settings

- Nutrition and WASH (including stunted growth)

- Advocacy and events on WASH & Nutrition

- Thematic Discussion on the SuSanA India Chapter - Convergent Actions for Improved WASH and Nutrition

Recently active users. Who else has been active?

Time to create page: 0.156 seconds